Table of contents

Open Table of contents

Introduction

Have you ever wondered what happens under the hood when a browser runs JavaScript code? In this article, I will explain the entire JavaScript runtime environment in the browser. How a JavaScript code is executed within the browser, and the artifacts within the environment that play their unique parts in running the script.

What is JavaScript Runtime Environment?

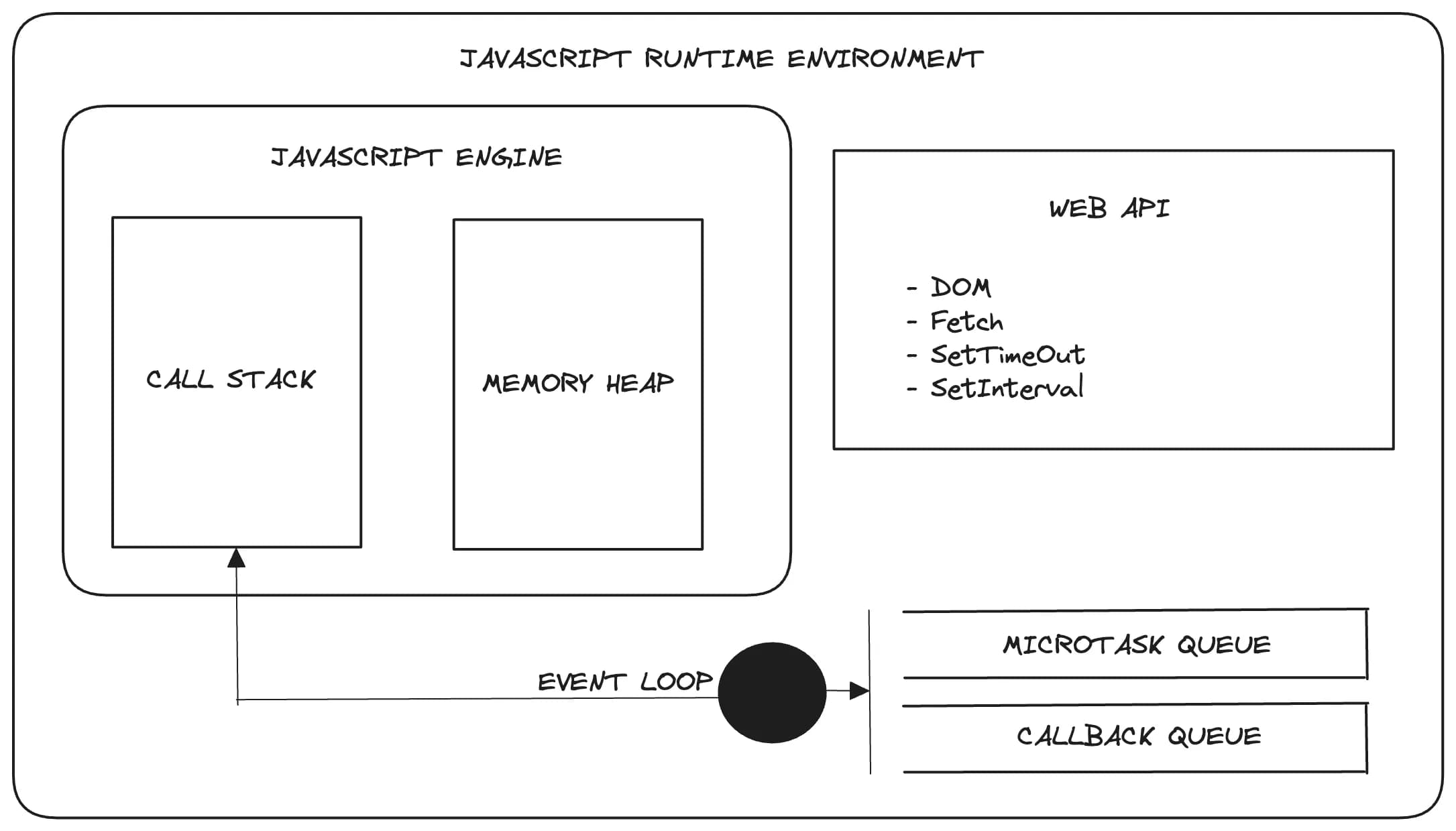

The JavaScript runtime environment refers to the platform in which JavaScript code is executed. This platform is composed of components which include:

-

JavaScript engine

- Call stack

- Memory heap

-

Browser features

-

Web APIs

fetch- Document Object Model (DOM)

setTimeoutsetInterval- And many more which can be found here

-

Macrotask queue

-

Microtask queue

-

Event loop

-

Figure 1: JavaScript Runtime Environment

Figure 1: JavaScript Runtime Environment

JavaScript Engine

The JavaScript engine is a program that parses, compiles and executes JavaScript code within the browser. Each major web browser has its own JavaScript engine, and there are also engines used outside of browsers, most notably in server-side environments like Node.js. Some of these engines include: Chrome V8 engine, SpiderMonkey, Chakra, and WebKit.

The execution of JavaScript code goes through two phases:

- parsing phase

- execution phase

Three things essentially happen during the parsing phase:

-

Tokenizing/Lexing: The JavaScript engine breaks down the code into meaningful tokens. Tokens are the smallest unit of a code, such as identifiers, literals, keywords, and operators.

-

Syntax Analysis/Parsing: Once the JavaScript engine breaks down the code into tokens, the engine constructs an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) using those tokens. The AST is a hierarchical structure of the code represented in a tree data structure, where each node in the tree corresponds to a construct in the code: variables, functions, expressions, etc. This tree helps the engine understand relationships and scopes within the code.

-

Error Checking: In addition to the above, the JavaScript engine, during the parsing phase, also checks for syntax errors. If it catches any syntax error that does not conform to JavaScript language rules, the execution is halted and an error is thrown. This is important because the engine does not move to the next phase of execution once this error is caught, hence improving the runtime performance of JavaScript code execution. Reference error is also caught during the parsing phase.

The JavaScript engine is composed of call stack, and memory heap.

Call Stack

A stack is a simple data structure that follows a Last In First Out (LIFO) order. The last item pushed into this data structure is the first to get out of it. Among others, there are essentially three important methods that are used to interface with a stack data structure: push(), pop(), and peek().

-

push()— The push method is used for adding an item to the stack -

pop()— It is used for removing the top most item in the stack, which is the last item added to it. -

peek()— it is used to see the top most item in the stack. The method does not remove the item.

In the context of JavaScript program execution, the call stack is a data structure that holds and keeps track of execution contexts (global and function(s) execution contexts). The JavaScript engine can only add the global execution context and function execution contexts to the call stack. When the JavaScript engine starts the execution of a JS code, it first creates the global execution context and pushes it onto the call stack. This execution context includes all the global states: variables and function definitions. It is the first to be pushed onto the stack, and the last to be popped out of the stack. Whenever a function is invoked in JavaScript, the engine creates a new execution context for that function and stores the states of that function in its local variable environment. These states can include: local variables, function definitions, arguments, and the value of this. After an execution context is created for that function, the engine then pushes it onto the call stack, sitting on top of the global execution context or any other function execution context that might have previously been created. Once the execution of a function call is completed, it is popped off the stack and the flow of execution is directed to the next execution context in the call stack; This continues till there are no more execution contexts in the call stack. For a better understanding of execution context, read my article, “JavaScript Internals: The Execution Context“ where I dived deep into JavaScript’s execution context.

Memory Heap

The memory heap in the JavaScript engine is a large pool and unstructured space of memory used for dynamically allocated memory. Within this space, the JavaScript allocates blocks of memory at runtime for objects, arrays, closures, and other dynamic data types. The JavaScript engine uses an algorithm to free up memory in the memory heap. This algorithm is known as the garbage collection algorithm. The garbage collector does a frequent scan in the heap to find dynamic data types (objects, arrays, closures, etc.) that no longer have references to them from the JavaScript code (i.e., no longer reachable), and frees those memories, making them available for future allocations. This essentially prevents memory leaks in the program.

Note: Memory heap should not be confused with heap data structure, because both of them are entirely two different things. The latter is a special tree based data structure that satisfies the heap property, where each parent node is either greater than or equal to or less than or equal to its child nodes.

Browser Features

JavaScript is a single threaded and synchronous programming language. Single threaded because only one task can be performed at the same time, and synchronous because tasks are executed one after the other in the order they appear lexically (physically) in the code, where the next instruction waits for the current instruction to complete before been executed.

How, then, are tasks performed in a non-blocking (asynchronous) way in JavaScript? Web APIs, macrotask queue, microtask queue, and event loop provides a mechanism for asynchronous actions to be performed. As you will be understanding better, please note that the Web APIs (fetch, setTimeout, and DOM, among others) are performed in the browser.

Note: Many a time, the terms “macrotask queue”, “macro task queue”, and “task queue” are often used interchangeably.

Web APIs

API stands for Application Programming Interface. Web APIs are built into the browser and helps developers incorporate features into a web application that native JavaScript does not support or provide out of the box. JavaScript uses these APIs to perform tasks outside the core language capabilities. These tasks can include Document Object Model (DOM) manipulations, AJAX calls, audio and video, geolocation, web storage, sensors and device access, and event handling, among others. This is an exhaustive list of the web APIs. I’ll explain three out of the very much web APIs that exist.

-

Fetch API: The fetch API is not a JavaScript core capability. It’s a browser feature that helps developers perform network requests in JavaScript code in a non-blocking way, whereby other tasks within the code are not blocked when the fetch API is initiated in the JavaScript code.

-

DOM: Document Object Model (DOM) is a tree structure and representation of the elements in an HTML document. It’s one of the Web APIs that provides a mechanism for developers to access and manipulate HTML elements from JavaScript code.

-

setTimeout: ThesetTimeoutis a Web API that provides an interface for developers to delay the execution of a task within a JavaScript code for a certain amount of time in milliseconds.function sayHello() { console.log("Hello!"); } setTimeOut(sayHello, 3000);The

setTimeOutin the above code is not built into JavaScript, it’s a browser feature that defers the invocation of thesayHellofunction for 3000 milliseconds, which is equivalent to 3 seconds.Will “Hello World!“ be printed on the browser console in 3000 milliseconds? As you will be understanding much better, the 3000 milliseconds does not tell us how long until

sayHellocallback function will be invoked. The 3000 milliseconds is how long before thesayHellocallback function is enqueued into the macrotask queue to be processed by the event loop.

Macrotask queue

Remember, I explained earlier that Web APIs are performed outside JavaScript, in the browser. Since they are performed outside the browser, how does the callback function associated with the operation gets placed back to JavaScript engine to continue execution? That’s exactly what I’m going to explain now, and in the subsequent sub topics.

console.log("Hello World!");

funtion printMessage() {

console.log("I am delayed for 3 seconds!")

}

setTimeout(printMessage, 3000);

console.log("End of code!");The above JavaScript code has a web API, setTimeout. Two parameters are passed to the setTimeout method above: a callback function and a delay time in milliseconds.

When the JavaScript engine runs the code above, a new execution context called the global execution context is created. Any global variable declaration and function definition is saved in the global execution context’s variable environment. In the code above, printMessage function definition will be saved in the global execution context’s variable environment.

When the JavaScript thread of execution reaches the setTimeout method, a new execution context is not created for the setTimeout function call because, setTimeout is an asynchronous operation that is not directly executed by the JavaScript engine but by the browser through its Web APIs. The browser sets up a timer and waits for 3000 milliseconds, and the JavaScript engine continues executing subsequent code without waiting for the timeout. Once the timer expires, the printMessage callback function is placed in a queue, known as the “macrotask queue“. When the call stack is empty, the first callback function in the macrotask queue is dequeued and pushed onto the call stack to be executed.

macrotask queue is a queue data structure in the JavaScript runtime environment that holds the callback functions of asynchronous operations performed by the browser.

Microtask Queue

Microtask queue is a type of task queue that has a higher priority than the macrotask queue. All the callback functions in the microtask queue are first processed (dequeued and pushed onto the call stack) before the ones in the macrotask queue.

What tasks are queued in the microtask queue? JavaScript promises and the Mutation Observer API callbacks are queued in the microtask queue.

Examples of operations that are enqueued in the microtask queue:

- Promise callbacks (

.then(),.catch(),.finally()). - Operations with

MutationObserver. - Other microtask sources like

queueMicrotask()function.

Event Loop

The job of the event loop in the JavaScript runtime environment is twofold. First, it continuously monitors the macrotask queue and microtask queue, for any callback from an asynchronous operation. It prioritizes callbacks in the microtask queue over the ones in the macrotask queue, meaning, it will first process/dequeue the callbacks in the microtask queue before processing the ones in macrotask queue. Second, it continuously monitors the call stack for when it is empty. If there are callbacks in the macrotask queue, the event loop will dequeue the first callback in the queue and push it onto the call stack (only if the call stack is empty i.e., when all the execution contexts, including the global execution context, have been popped out of the call stack).

Example

Let’s explore an example to further solidify our understanding on the concepts explained.

console.log("Start!");

setTimeout(printHello, 1000);

const fetchTodos = fetch("https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/todos");

fetchTodos

.then(function toJSON(data) {

return data.json();

})

.then(todos => printTodos(todos));

function printHello() {

console.log("Hello!");

}

function printTodos(todos) {

console.log(todos);

}

console.log("End!");Below are the parsing and execution steps of the code above:

-

Upon execution of the code above, the global execution context is created and pushed unto the call stack. The functions

printHelloandprintTodostogether with their entire function block are hoisted at the top of their containing scope, which is the global scope and saved in their variable environment. That is why the JavaScript engine did not raise an exception even though the two functions were referenced before their declarations. The variablefetchTodosis hoisted as well, but it remains in an unreachable state, which is called the Temporal Dead Zone (TDZ). For more on hoisting, I suggest you read my articles on hoisting — Hoisting in JavaScript: A Complete Guide, Part 1 and Hoisting in JavaScript: A Complete Guide, Part 2 -

As the engine starts executing the code line by line, “Start!“ is first printed. Immediately

setTimeoutis invoked, the engine does not create an execution context for it, because it’s not a native JavaScript feature. The JavaScript engine delegates thesetTimeoutresponsibility to the browser, because it’s a Web API. All Web APIs are handled by the browser. -

Our

setTimeouthas two arguments:printHelloand 1000.printHellois the callback function, and 1000 is the delay time — the time it takes for the callback function to be enqueued into the macrotask queue. -

Since

setTimeoutis a non-blocking operation, the thread of execution moves to the next line, and once it gets to thefetchcall, a new execution context is not created, because it’s a browser feature (Web API), and that responsibility is delegated to the browser by the JavaScript engine. ThefetchAPI is an ES6 promise, which is a non-blocking task, hence our code will not be blocked. -

The thread of execution continues, and “End!“ is printed.

-

What about our

setTimeoutandfetchTodos? Remember they are all asynchronous operations, which are performed by the browser. Each of these operations have a callback function that should be executed after the asynchronous tasks are completed by the browser. How do these callback functions:printHello,printTodos, andtoJSONallowed back into the call stack for execution? -

Recall that microtask queue has a higher priority that macrotask queue. Tasks in microtask queue are first processed by the event loop before the ones in macrotask queue.

-

Assuming the network request to fetch to-dos completes in 1000 milliseconds, the same time with the

setTimeoutdelay time,printTodos(todos)(the result of thefetchoperation) will be printed to the console beforeprintHello()(thesetTimeoutcallback). The reasons are because:- The callback for

setTimeoutis considered a macrotask. Once the specified delay has elapsed, it is placed in the macrotask queue, waiting for the execution turn. - The

.then()callbacks attached to afetchpromise are considered microtasks. Upon successful resolution of the promise (e.g., when the network request completes), the callbacks are placed in the microtask queue. - The event loop processes all tasks in the microtask queue after the currently running script has completed before processing the tasks in the macrotask queue. This means that all pending microtasks are processed before the processing of macrotasks.

- The callback for

-

Below is the order of the logs on the console:

- Start!

- End!

- [Array of to-dos] or Hello!, depending on the factor below:

- [Array of to-dos] is printed first if it took the

fetchAPI less than or equal to 1000 milliseconds to complete the network request, and its callbacks added to the microtask queue before thesetTimeoutcallback is added to the macrotask queue. Otherwise, “Hello!“ will be printed first before [Array of to-dos]

- [Array of to-dos] is printed first if it took the

Conclusion

The JavaScript runtime environment is a complex and finely tuned platform that powers the execution of JavaScript code in browsers and beyond. From capabilities of the JavaScript engine to the asynchronous orchestration of tasks via the event loop, microtask and macrotask queues, and the utility of Web APIs, we’ve delved into the core components that make JavaScript uniquely powerful and versatile.

Understanding these internals equips you with the knowledge to write more efficient, non-blocking code. By leveraging the event loop and understanding the nuances of task scheduling, you can harness the full potential of JavaScript, enhancing both the performance and the user experience of your applications.

Whether you aspire to be a frontend, backend, or full-stack developer, mastering the nuances of the JavaScript runtime environment is a significant milestone on your journey. This knowledge will help you write code that works harmoniously within the ecosystem that JavaScript operates in, ensuring your applications are scalable, responsive, and efficient.

Let this exploration be a stepping stone towards mastering JavaScript in-depth. The more you understand the environment in which your code runs, the better equipped you’ll be to tackle the challenges of modern web development head-on. Keep experimenting, keep learning, and keep building. Thank you, and see you in my next article 😊👋.