Table of contents

Open Table of contents

Introduction

A quick question before we take a deep dive into the topic of discussion. In JavaScript, can you use a variable before it’s defined and initialized? If you answered yes, you are not far from the right answer, and if you answered No, you are not entirely wrong. There are nuances to the fact that a variable can be used before it’s defined in JavaScript. Have a look at the code below.

console.log(fullName); // undefined

var fullName = "Sixtus Innocent";The JavaScript engine will not throw a ReferenceError exception when the code above gets executed, even though the identifier fullName is referenced before it’s defined and initialized. What gets printed on the browser console after executing the code is undefined. How is this possible? It’s possible because of a JavaScript feature called hoisting.

Let’s take one more example. Consider the code below. The JavaScript engine will not halt the execution of the code by throwing a ReferenceError exception, even though the function sayHi is referenced and invoked before its declaration. Again, this is possible because of hoisting. Hi, Sixtus! is finally printed on the browser console, without the engine throwing a ReferenceError exception.

sayHi(); // "Hi, Sixtus!"

function sayHi() {

console.log("Hi, Sixtus!");

}As mentioned earlier, there are nuances to hoisting. Variables are hoisted differently depending on the variable declaration keyword used. For example, const and let are hoisted differently from var, and function expression is hoisted differently from function declaration.

What is Hoisting?

To hoist means to raise (something) by means of ropes and pulleys. In MDN Web Docs, hoisting is defined as, the process whereby the interpreter appears to move the declaration of functions, variables, classes, or imports to the top of their scope, prior to execution of the code. I know you might be a bit lost If you are new to this concept. I will try to give a mental picture of what hoisting is like with examples. In programming language, a scope is where states (variables and functions) can be accessed.

// Global Scope

greeter();

function greeter() {

// Function scope

greet = "Good morning";

firstName = "Sixtus";

console.log(greet + ", " + firstName); // "Good morning, Sixtus"

var greet;

var firstName;

}Note these points that are true about the code above:

- Function declaration:

function greeter() {...} - Variable declarations:

var greet,var firstName - Variable assignments:

greet = "Good morning",firstName = "Sixtus" - Two scopes: block scope and function (or local) scope

I want you to picture and see as though the JavaScript interpreter lifts all the function declarations and variable declarations to the top of their respective scopes (global and function scopes) before executing the code. Hence, the code will be re-evaluated/re-written like this:

// Global scope

function greeter() {

// Function scope

var greet;

var firstName;

greet = "Good morning";

firstName = "Sixtus";

console.log(greet + ", " + firstName); // "Good morning, Sixtus"

}

greeter();Note: The JavaScript engine does not re-write the code, this is an analogy to help you understand hoisting.

Hoisting Rules

Let’s establish the different rules the interpreter uses to hoist different types of identifiers when executing a JavaScript code. I will use these rules as listed below to explain with examples how the interpreter performs hoisting. Below are the rules:

- Rule 1: Variables declared with

varkeyword are hoisted (lifted) to the top of their containing scope, and if they are initialized a value, that value will not be lifted as well, but rather the engine will initialize a default value ofundefinedfor that variable identifier. - Rule 2: All the entire function declarations are hoisted (lifted) to the top of their containing scope. Hence, function declarations can be invoked before they are declared in the code.

- Rule 3: Variables declared with

letandconstare hoisted (lifted) to the top of their scope, which is block scope, but the engine does not initialize a default value to them like the way it does withvar. The JavaScript engine throwsReferenceErrorwhen these variables are accessed before their declaration. The state before the line of declaration is reached is known as the Temporal Dead Zone (TDZ). - Rule 4: Function expressions follow the hoisting rules of the variable (let, const, or var) they are assigned to. If a function expression is assigned to a

vardeclared variable, the variable declaration is hoisted but not the assignment as seen in rule 1, and if assigned to aletorconst, they will remain in the TDZ state until their declaration line is executed as seen in rule 3. - Rule 5: Class declarations are hoisted similarly to

letandconst. Their declaration is hoisted without their initialization, hence you cannot instantiate them before the declaration is reached in the code.

Variables Declared with var vs Ones Declared with let or const

Variables declared with the var keyword are hoisted as well as those declared with let and const, but there are nuances to how they are hoisted. Let’s delve into few examples.

console.log(pet); // undefined

var pet = "cat";

console.log(pet); // catWhen we run the code above, the JavaScript engine will first print undefined on the browser console. Remember our hoisting rules? What rule does this behaviour fall under? It falls under the rule one of the hoisting rules we established earlier. Variables declared with the var keyword are hoisted without their initialized values, and are initialized a default value of undefined by the JavaScript engine. Mirroring what the interpreter appears to do with the code above, it will look somewhat like this.

var pet;

console.log(pet); // undefined

pet = "cat";

console.log(pet); // catLooking at the above code, you will observe that the variable pet was lifted without its default initialization of “cat“ to the pet identifier, hence the first output seen on the console being undefined.

What happens when a variable declared with the ES6 let or const keyword is referenced before its declaration? Variables declared with the let or const keywords fall under rule 3 for how they are hoisted. They are hoisted (lifted) to the top of their scope but the engine does not initialize a default value to them like the way it does with var.

console.log(pet);

let pet = "cat";

console.log(pet);The variable pet will be hoisted but it will remain in a state where it’s unreachable if referenced before its declaration. This state is known as Temporal Dead Zone (TDZ). The engine will raise a ReferenceError exception when the pet identifier is referenced before its declaration. I will write a part two of this article to clearly explain TDZ.

Function Declaration vs Function Expression

Are function expressions and function declarations hoisted the same way? No, they are not. Function expressions are functions that are assigned to a declared variable using either var, let, or const keyword. If a function expression is declared using var it will be hoisted using rule 1, and if it’s declared using let or const, it will be hoisted using rule 3. Let’s explore a few examples.

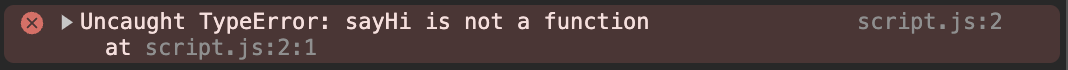

sayHi();

var sayHi = function printHi() {

console.log("Hi, Sixtus!");

};

sayHi is an identifier for a named function expression, called printHi. The JavaScript engine throws a TypeError exception when it executes the code above, as seen in the browser console log above. Notice that it’s not a ReferenceError, which means that the variable sayHi was hoisted and assigned a value. What value did the engine assign it to during hoisting? It was assigned undefined, because JavaScript assigns all variables with the var keyword that are hoisted a default value of undefined (see rule 1 of hoisting). So when var sayHi is lifted, it becomes var sayHi = undefined. Hence, invoking sayHi which is of type undefined will throw a TypeError exception by the engine, because undefined is not a function and cannot be invoked.

Let’s consider invoking the function this way:

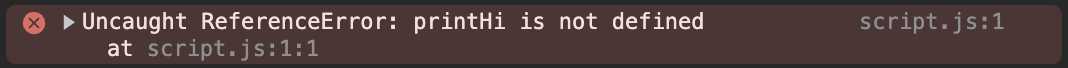

printHi();

var sayHi = function printHi() {

console.log("Hi, Sixtus!");

};

Oh, my! The engine throws a different kind of exception. This time it’s ReferenceErrorexception, because printHi is not defined anywhere in the code. Recall that because of hoisting, the engine appears to lift var sayHi up its scope, which is the global scope, and then assigns it a default value of undefined, because it’s defined using the var keyword. Let’s rewrite the code like how the interpreter would have appeared to rewrite it.

var sayHi = undefined;

printHi();

var sayHi = function printHi() {

console.log("Hi, Sixtus!");

};After rewriting the code, which appears to be what the interpreter does, but not actually true, we can see that the var sayHi is lifted and assigned a default value of undefined. The invocation of printHi() will throw a ReferenceError exception, which it does actually, because printHi is not an identifier within the global scope, and cannot be referenced anywhere within the code.

What about function declarations? Do you recall our greeter function? Our greeter function is a function declaration. Rule 1 of our hoisting rules defines the way function declarations are hoisted. They can be invoked before they are declared lexically in the code without the engine throwing an exception. Okay, Let’s revisit the greeter function.

// Global Scope

greeter();

function greeter() {

// Function scope

greet = "Good morning";

firstName = "Sixtus";

console.log(greet + ", " + firstName); // "Good morning, Sixtus"

var greet;

var firstName;

}Unlike how function expressions are hoisted with a default value of undefined if assigned to a variable declared with a var keyword, function declarations are hoisted with their entire function declarations. The JavaScript engine will seemingly lift the entire function declaration before it’s invocation, hence the reason the engine was still able to access the greeter function despite been referenced before its declaration. The code above will look like the code below when hoisted.

// Global scope

function greeter() {

// Function scope

var greet;

var firstName;

greet = "Good morning";

firstName = "Sixtus";

console.log(greet + ", " + firstName); // "Good morning, Sixtus"

}

greeter();What About Variable Redeclaration using var, let, and const?

Consider the code below:

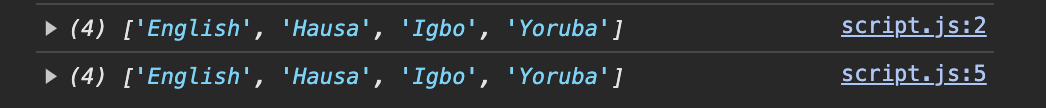

var languages = ["English", "Hausa", "Igbo", "Yoruba"];

console.log(languages);

var languages;

console.log(languages);Notice the variable redeclaration of languages. What gets printed to the browser console?

The second log to the browser console is not undefined as you might have thought, it’s still the initialized array of language in the first declaration. This is possible because of hoisting, and how the JavaScript engine appears to lift variable declarations, function declaration, and classes to the top of their scope. Let’s re-arrange the code to mirror how the engine would have supposedly rearranged it.

var languages;

var languages;

languages = ["English", "Hausa", "Igbo", "Yoruba"];

console.log(languages); // ["English", "Hausa", "Igbo", "Yoruba"]

console.log(languages); // ["English", "Hausa", "Igbo", "Yoruba"]From the above, we can conclude that when an identifier declared with the var keyword is redeclared and not initialized with a default value, it does not override the initial declaration in the code. What if we redeclare and initialize the identifier ‘language’ with a default value, as seen in the code below?

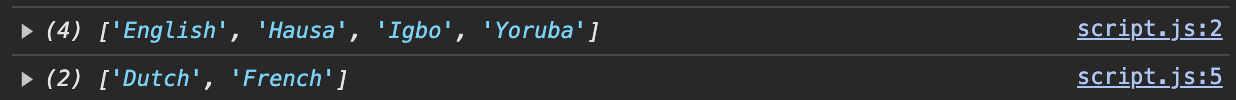

var languages = ["English", "Hausa", "Igbo", "Yoruba"];

console.log(languages);

var languages = ["Dutch", "French"];

console.log(languages);

I know you guessed the answer right! Any variable redeclared and initialized with the var keyword, the engine will override the value of the previous variable that sits lexically (physically) within the same scope.

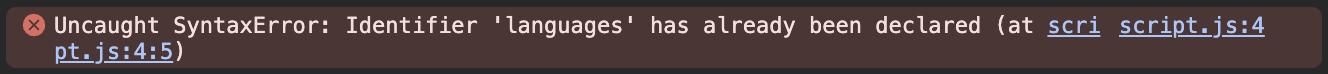

Let’s consider more examples with let

let languages = ["English", "Hausa", "Igbo", "Yoruba"];

console.log(languages);

let languages = ["Dutch", "French"];

console.log(languages);

It appears that the code didn’t reach the execution phase, because of the type of exception thrown by the JavaScript engine. SyntaxError are caught early by the interpreter during the paring phase before code execution. This means that redeclaration is not allowed with the let keyword.

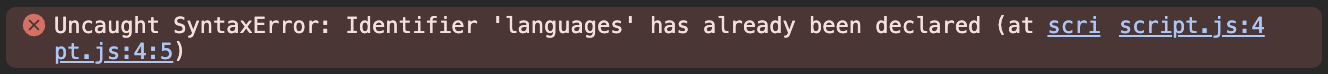

Let’s redeclare with let and var, and vice versa.

let languages = ["English", "Hausa", "Igbo", "Yoruba"];

console.log(languages);

var languages = ["Dutch", "French"];

console.log(languages);

var languages = ["English", "Hausa", "Igbo", "Yoruba"];

console.log(languages);

let languages = ["Dutch", "French"];

console.log(languages);

The same SyntaxError raised using only let is raised for the two cases where var is used after let for redeclaration and vice-versa.

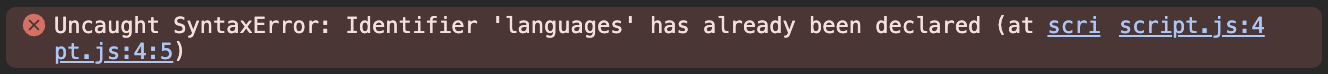

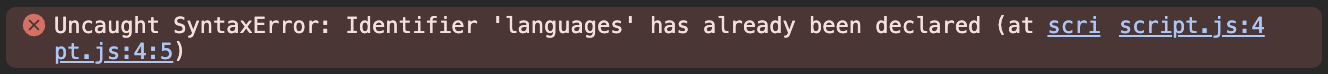

Finally, let’s see if redeclaration is possible using const

const languages = ["English", "Hausa", "Igbo", "Yoruba"];

console.log(languages);

const languages = ["Dutch", "French"];

console.log(languages);

The above SyntaxError exception raised by the JavaScript engine is a clear indication that the engine does not support variable redeclaration with the const keyword. The same SyntaxError exception raised above will be raised when a variable is declared with const and not initialized at the same time. What happens if a variable declared and initialized with the constkeyword is reassigned a value? Consider this example:

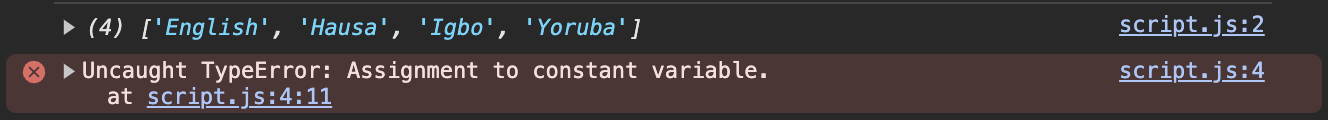

const languages = ["English", "Hausa", "Igbo", "Yoruba"];

console.log(languages);

languages = ["Dutch", "French"];

console.log(languages);In the above code, languages is being reassigned a value. When the engine reaches that line while executing the code, it will halt, and throw a TypeError exception as seen below, because const cannot be reassigned a value.

While SyntaxError is thrown during the parsing phase of JavaScript code, TypeError is thrown during the execution phase, hence the reason for the log on the browser console of the first languages.

Conclusion

Hoisting is a very important topic in JavaScript that, if grasped, will help us write better and safe code. This ensures that our code will be more predictable and more organized, hence facilitating debugging. Hoisting is foundational for understanding advanced concepts like closures, execution contexts, and the temporal dead zone.

I will publish the part two of this article where I will write about temporal dead zone, and how classes are hoisted, among others.

Thank you!